More Powerful than Lies: Taiwan's 2025 Recall Campaign and the Rise of AI-Generated Mini Clips

Authors:Wei-Ping Li, Summer Chen, Mary Ma

Full Text Download English Mandarin

Summary

In 2024, with 74 national elections worldwide, the rise of AI has sparked concerns that AI-generated false information could interfere with elections, as AI makes creating and spreading false content easier. After the election, experts continue debating whether the worries about AI's impact on elections are justified. However, a months-long recall campaign in Taiwan in 2025 has raised another concern about AI — specifically, AI-generated mini-clips with eye-catching footage that often blur the line between truth and falsehood, capable of swaying voters by provoking strong emotions.

FactLink discovered that during the 2025 Taiwanese recall campaign, short AI mini-clips, many created and edited with Chinese AI tools and featuring photorealistic or animated images, were widely circulated as Reels clips on Facebook and Instagram. These mini-clips were used to mock and attack politicians or citizen groups. These images attracted significant attention on social media, being widely liked and shared.

In this study, the FactLink team analyzed 318 AI-generated online mini-clips about the 2025 Taiwanese recall event from April 25 to July 30, 2025, focusing on their propaganda tactics, recurring symbols in the content, and AI tools that generated these images. We also examined how often these clips were viewed, shared, and liked on social media, as well as how audiences responded to the propaganda.

After an extensive review of the clips, we conclude that these AI-generated mini-clips pose even greater challenges to democratic societies than false claims that fact-checkers can more effectively debunk. We call on researchers, fact-checkers, journalists, NGOs, policymakers, and stakeholders in democracies to recognize this trend and collaborate on finding solutions.

Key findings

AI-generated mini-clips went viral as Reels and were promoted by Facebook and Instagram during the 2025 Taiwanese recall campaign.

Unlike TikTok videos, which typically last 35 seconds to a few minutes, the viral mini-clips during the 2025 Taiwanese recall were extremely short, lasting only a few seconds. We refer to this new genre of very short videos as "mini-clips" in this research. During the recall campaign, they were primarily shared as Reels and boosted on Facebook and Instagram, promoted by these platforms' algorithms.

The mini-clips depicted individuals or groups using simplified and demeaning figures and images, frequently blurring the distinction between truth and falsehood, which easily provoked emotional responses from viewers.

The mini-clips were very short, leaving little space for detailed stories. Their main aim was to create a strong visual impact and effectively deliver messages that could provoke emotions. Although many mini-clips still encouraged citizens to vote on recall day, a large portion of clips spread negative content to mock politicians, groups, or ordinary citizens who supported the recall of legislators, smeared opponents by twisting facts, invented entirely fictional events, or created divisions between social groups or generations. For example, some clips ridiculed politicians for personal gain and mocked those supporting the recall of legislators as acting without agency.

The most-watched mini-clips encouraged voters to cast their ballots, while the most widely shared ones made up fictional events to mock recall supporters or politicians.

Our analysis revealed that the most-watched mini-clips encouraged viewers to vote and share their political opinions. However, clips employing negative tactics, such as ridiculing opponents, fostering social or generational divisions, or attacking politicians, received more "likes" and were shared more often. Additionally, the most widely shared category involved clips that created non-existent events to mock influencers, political groups, or politicians.

Many AI-generated mini-clips were produced by Chinese AI tools.

We traced the creation process of these AI-generated mini-clips by analyzing watermarks on the images. We found that many were produced using Chinese AI content-generation tools and editing software, which helped speed up footage creation. With AI tools, different producers could generate various clips and scenes following the same script. The process was so simple that similar videos could be produced quickly. Interestingly, these mini-clips didn’t even try to hide the signs of AI, indicating they weren’t worried about being seen as untrue. Instead, their primary goal was to make an impression, provoke emotions, and reinforce viewers’ perceptions and attitudes.

AI mini-clips have emerged as a tool for political propaganda. Through repeated visual symbols, they discourage rational debate by replacing thoughtful deliberation with quick stereotype validation and emotional responses. For researchers studying information manipulation, tracking AI mini-clips poses a significant challenge due to their ease and speed of creation. Moreover, their blend of facts and misinformation, along with their capacity to suggest misleading implications, creates difficulties not only for fact-checkers but also for media literacy educators.

I. The Context: The 2025 Taiwanese Recall

The 2025 recall voting in Taiwan on July 26, commonly referred to as the "Great Recall," aimed to remove more than 20 lawmakers from the Kuomintang Party (KMT) in the Legislative Yuan and one local mayor from the Taiwan People's Party (TPP). Many of those targeted faced criticism for their close connections to China and were viewed as potential threats to Taiwan's national security. These KMT lawmakers also supported a deep cut in 2024 that drastically reduced the national budget, impacting defense, central government operations, and education.1

Discontent with these KMT legislators led to large protests called the "Bluebird movement"2 in May 2024 and fueled efforts to recall the legislators along with the Hsinchu city mayor, who was deemed unfit for office. Taiwanese law allows citizens to recall elected officials, but the requirements are strict. The first recall election took place on July 26. However, none were successfully recalled.3 A second recall targeting seven KMT legislators is scheduled for August 23, 2025.

II. AI-generated mini-clips as a propaganda tool

In 2024, AI tools were already used in election campaigns to create short videos aiming to rebrand candidates' images, increase their popularity, or mock opponents. For example, Indonesia's Prabowo Subianto, a former military officer with a controversial history of human rights abuses from decades earlier, gained popularity among Indonesian youth by releasing AI-generated footage showing him as a "cuddly grandpa" dancing with funny moves.4 In the United States, an AI-generated fake video in which Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris claimed to be "the ultimate diversity hire" was also promoted by Elon Musk and widely shared online. 5During the 2025 Taiwanese recall campaign, we further found evidence that AI was used to produce extremely short mini-clips—lasting from 5 to 30 seconds—as propaganda tools to influence and persuade voters.

We observed that AI-generated mini-clips were frequently displayed to social media users while they scrolled through other themes of Reels videos featuring current events, entertainment, and everyday life clips. What distinguished the AI-generated mini-clips from typical short videos was their length. TikTok and other social media short clips usually last 30 seconds to several minutes, sufficient for brief stories or sharing opinions. In contrast, AI-generated mini clips were much shorter—ranging from 5 to 30 seconds—making them resemble "moving pictures" that are slightly longer than GIFs.

In the next section, we will cover seven information manipulation tactics used by these mini-clips during the 2025 Taiwanese recall campaign.

III. The Tactics

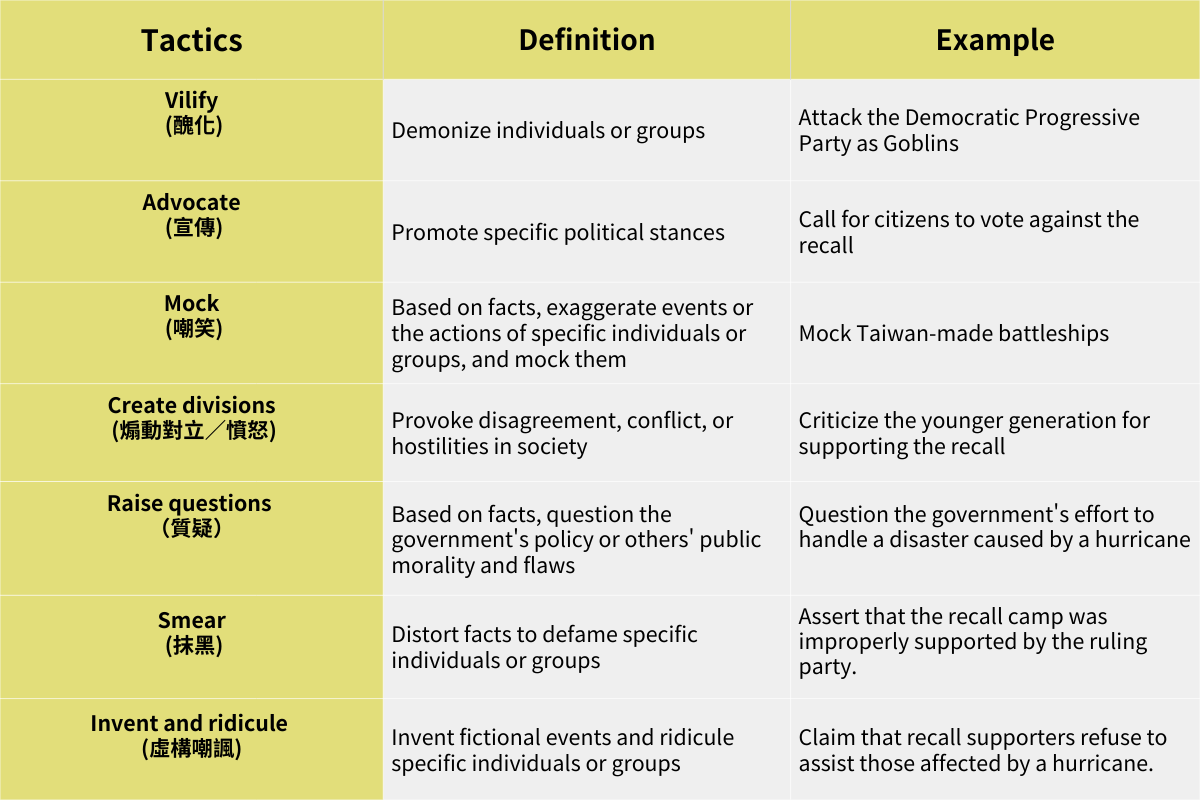

We examined 318 posts and mini-clips, identifying seven tactics they employ to sway viewers.

AI mini-clips most often demonized the pro-recall camp, including politicians, influencers, and supporters of the recall. Another common tactic is to promote opposition to the recall, aiming to boost morale and encourage a "no" vote among those against the recall. Often, the clips featured attractive women and cheerful crowds to persuade people to vote "no."

Other tactics used in these AI-generated mini-clips included fabricating fictional events or exploiting news stories to criticize the government's policies or highlight individuals' moral flaws. We also saw content that slandered opponents with false information or incited conflicts among social groups or generations.

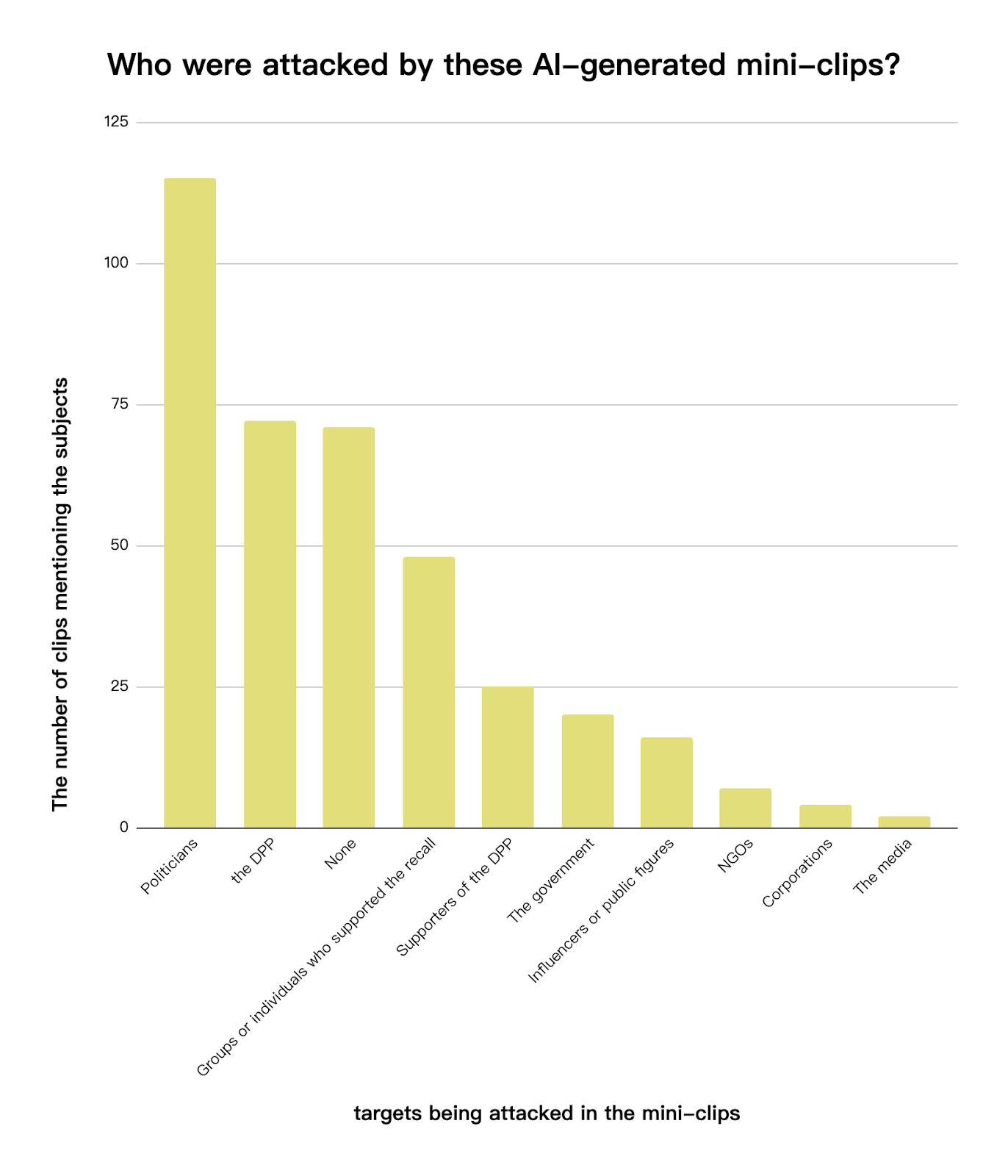

The most targeted subjects in these AI-generated mini-clips were politicians, such as Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te and several legislators from the ruling party, followed by the ruling party itself, the DPP. These clips primarily attacked the politicians' morality, such as claiming that President Lai intended to establish a dictatorship in Taiwan or suggesting that there were inappropriate romantic relationships among the alleged legislators. Additionally, the clips also targeted recall supporters, often mocking them as mindless tools controlled by politicians.

IV. The Symbols

Influencing through distinct symbols and images

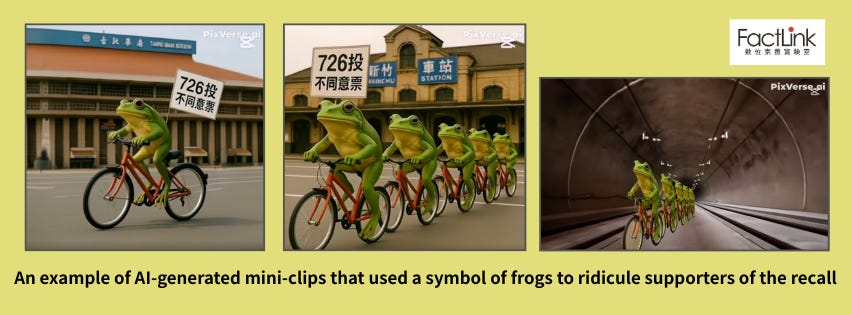

A key aspect of the AI-generated mini-clips was their use of symbols to convey concise yet impactful messages. The creators focused on influencing viewers' perceptions of the subjects rather than telling stories to persuade. For instance, supporters of the recall were shown as ugly toads, aggressive birds, or mindless zombies.

These symbols carried specific meanings. The images of "frogs" or "toads" originated from a nickname coined by Chinese "little pink" patriots for Taiwanese people, implying that the Taiwanese are like frogs or toads living at the bottom of wells and unaware of the wider world. Notably, the AI mini-clips employed an even more insulting symbol, the "flying frog," to criticize supporters of the recall. Additionally, President Lai Ching-te was shown with his tongue out, also referencing the "frog" nickname.

The mixture of facts and fiction

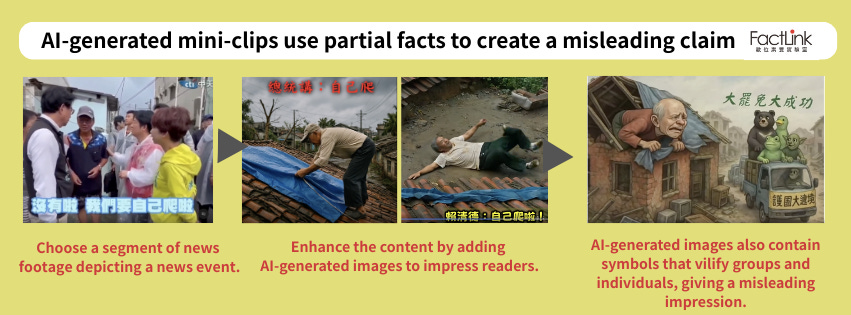

Another significant feature of these AI-generated mini-clips was that they exploited news events and blended facts with fictional content, leading to misleading claims.

For instance, a strong hurricane hit southern Taiwan, causing major damage weeks ahead of the recall vote. When a victim told President Lai about the slow disaster relief, Lai advised that victims could try DIY repairs until external help arrived. Later on, there were reports of elderly individuals trying to fix their roofs on their own and dying from falls. Lai's controversial advice triggered further public dissatisfaction.

Multiple AI-generated mini-clips used Lai's response to create Reels, showing senior victims climbing onto the roof, with symbols like blue birds, black bears, and frogs representing recall supporters celebrating on the other side. The claim that recall supporters ignored hurricane disaster relief was false. However, the clip shared by an account with only 10,000 followers was viewed 2.43 million times and shared 1,300 times, illustrating the effectiveness of this type of clip that leveraged trending events and was amplified by Reels' algorithms.

V. The Tools

The watermarks on these AI-generated mini-clips revealed insights into their creation process. The FactLink team traced these watermarks and found that Chinese AI tools accelerated the production and editing of these clips. Several clips showed similar content or scenes with minor variations, indicating they may originate from a single prompt or script. AI technology has enabled the rapid production of numerous mini-clips with interchangeable variations. Notably, many clips displayed transparent 'AI-made' marks such as logos of the AI tools, indicating they were not intended to deceive viewers into thinking they were real, but were meant to leave an impression and shape perception.

Following our examination of these watermarks, we identified three key findings:

Many of the mini-clips were created or edited with Chinese AI tools.

A single clip might involve multiple AI tools, leaving behind traces of the production process.

Some clips closely resembled each other, suggesting they copied one another in a short period of time.

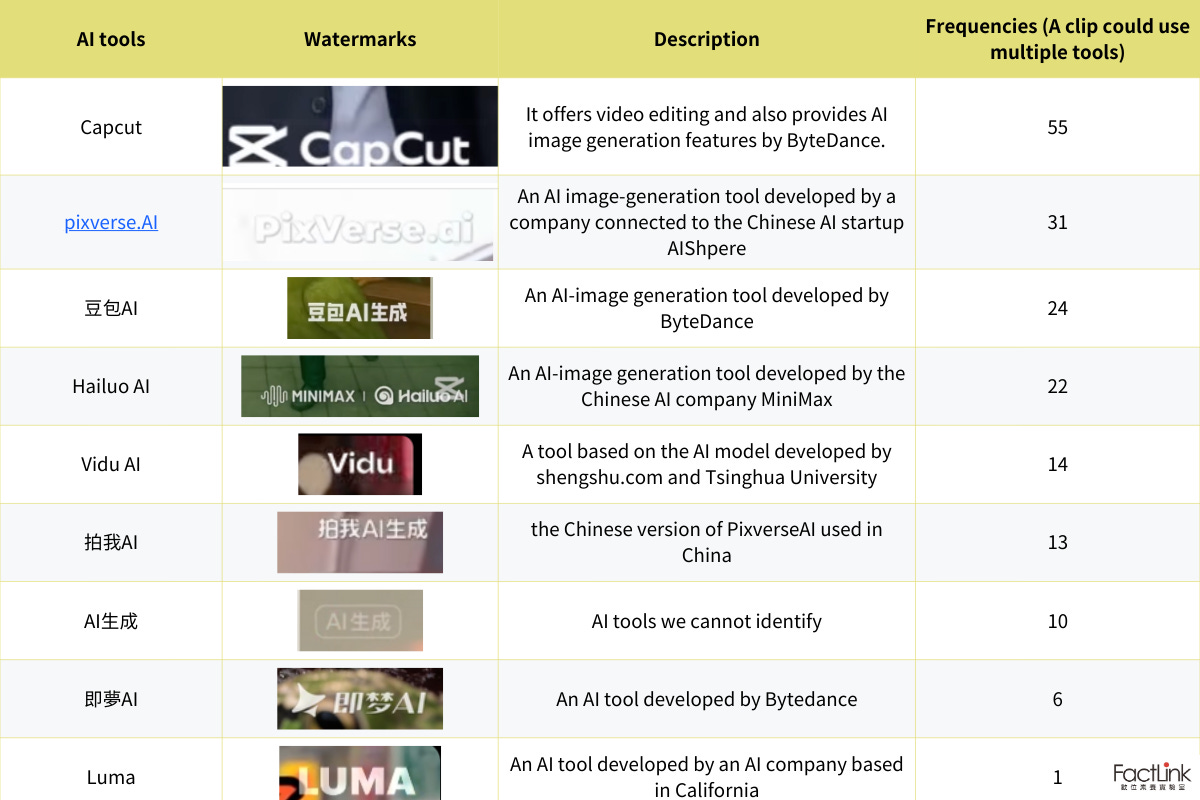

Mini-clips by Chinese AI tools

Among the 318 AI-generated mini-clips, 112 of them (35.3%) had watermarks indicating they were created with certain AI tools, including CapCut、Luma、ViduAI、Pixverse.AI、拍我 AI(pronounced as "Pāi wǒ" AI)、豆包AI (Doubao AI)、即夢AI (Dreamina AI)、Hailuo. Some of the clips were labeled with "AI-made" but did not specify which AI tools were used to produce them.

Most AI tools were developed by Chinese companies or were "international versions" of Chinese video AI tools. For instance, 豆包AI (Doubao AI), ViduAI, 即夢AI (Dreamina AI), 拍我AI (Pai wo AI), and Hailuo AI are all Chinese AI products. CapCut is the global version of the Chinese editing software 剪映 (JianYing), and Pixverse.AI is the international version of 拍我 (Pai wo AI).

A single clip can be created using multiple AI tools.

Our analysis revealed that 61 mini-clips (19.2% of all clips) contained more than two watermarks, and 26 clips (8.2%) had over three watermarks, indicating they underwent multiple production stages.

The analysis also showed that CapCut was the most commonly used AI tool, often alongside other tools. Yu-chen Dai and Chung-Yi Zeng, AI experts from Taiwan's National Institute of National Security, explained to FactLink that CapCut was primarily employed for video editing and post-production. Creators of these mini-clips might initially use different AI tools to generate images, then utilize CapCut to insert text or incorporate additional authentic images.

For instance, to portray the pro-recall group as being manipulated by politicians, a mini-clip was created showing "the pro-recall group taking a bus to protest mainly for free food, then being dismissed because of rain." The process first used Doubao to generate cartoon-like bluebird images lining up for food, and then used CapCut to add real video footage.

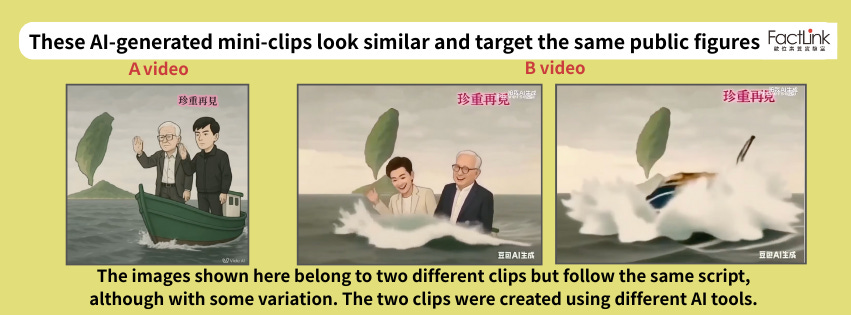

The resemblances among the mini-clips

AI generation tools allow multiple accounts to quickly duplicate, modify, or collaborate on content within a short timeframe. We observed that many of these AI-created mini-clips shared common visual elements and scenes. For example, several videos showed an image of a "frog riding a bicycle," a symbol often used derisively for recall supporters, paired with the message "Vote No on 726," set against various city backdrops like Taipei Main Station, Hsinchu Station, and the Ziqiang Tunnel. This series of similar clips created the visual impression that "Taiwan frogs" were ubiquitous.

In another example, two videos depicted public figures supporting the recall, Tsao Hsing-cheng (曹興誠) and Bajiong (八炯), leaving Taiwan on a small boat with the caption "Farewell" and the background music "Green Island Serenade." (Note: "Green Island Serenade" is a well-known Taiwanese ballad historically associated with political imprisonment on Green Island during martial law.) These videos mocked the failure of the recall groups following the recall election. The word "Farewell" was even taken from a personal video Bajiong posted on Threads after the recall concluded.

The analysis shows that the initial video, posted by account A on July 28 via ViduAI, only depicted the two individuals waving goodbye. The "enhanced" version by account B, released on July 30, combined visual effects made by "Paiwo AI" and "Doubao (豆包) AI" to include a new scene where the boat sinks and the two are submerged in seawater. These examples demonstrate that AI technology has sped up the dissemination and adaptation of political propaganda content.

VI. The Effects: Were AI-generated mini-clips popular and widely shared among viewers?

In this study, we analyzed the number of views, likes, and shares of these AI-generated mini-clips to understand how viewers engaged with them.

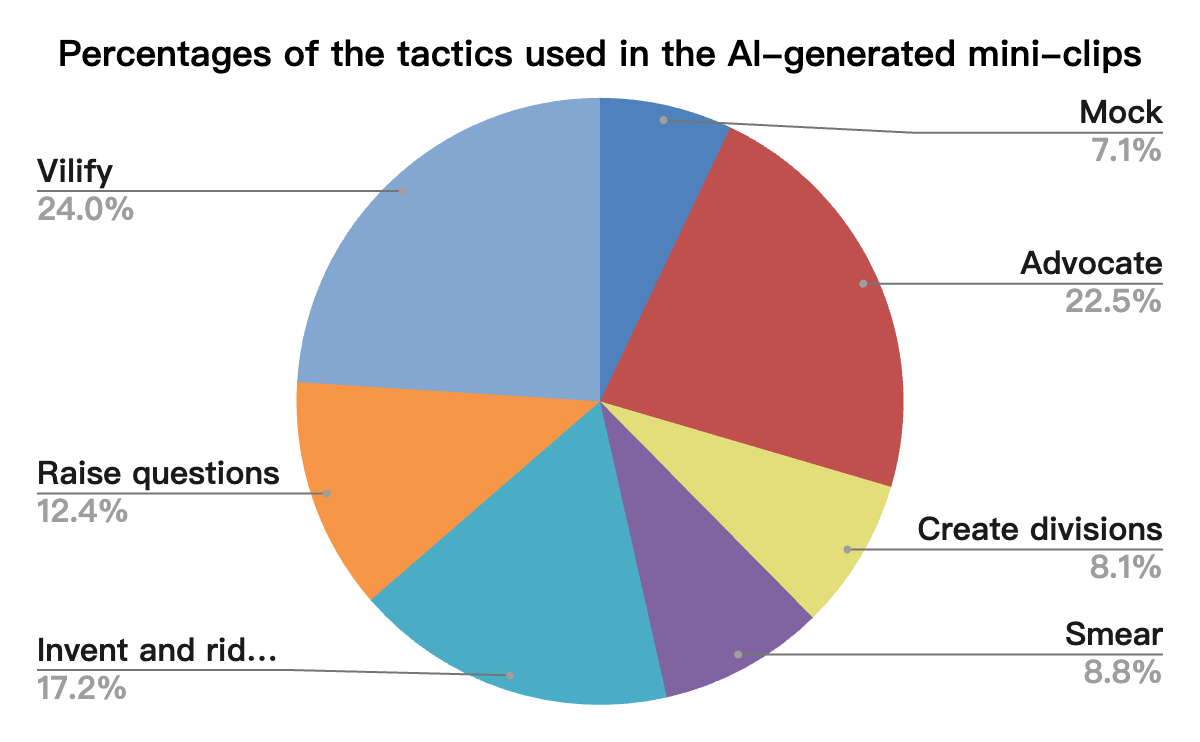

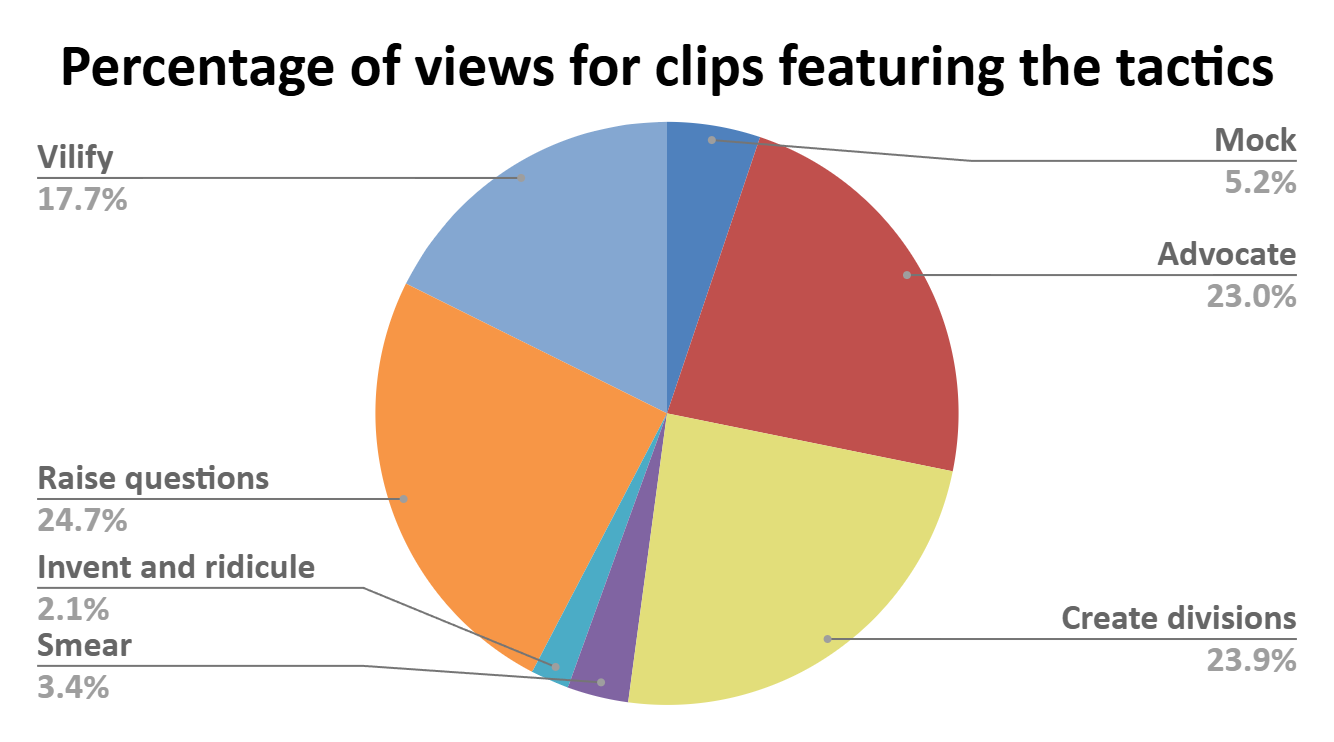

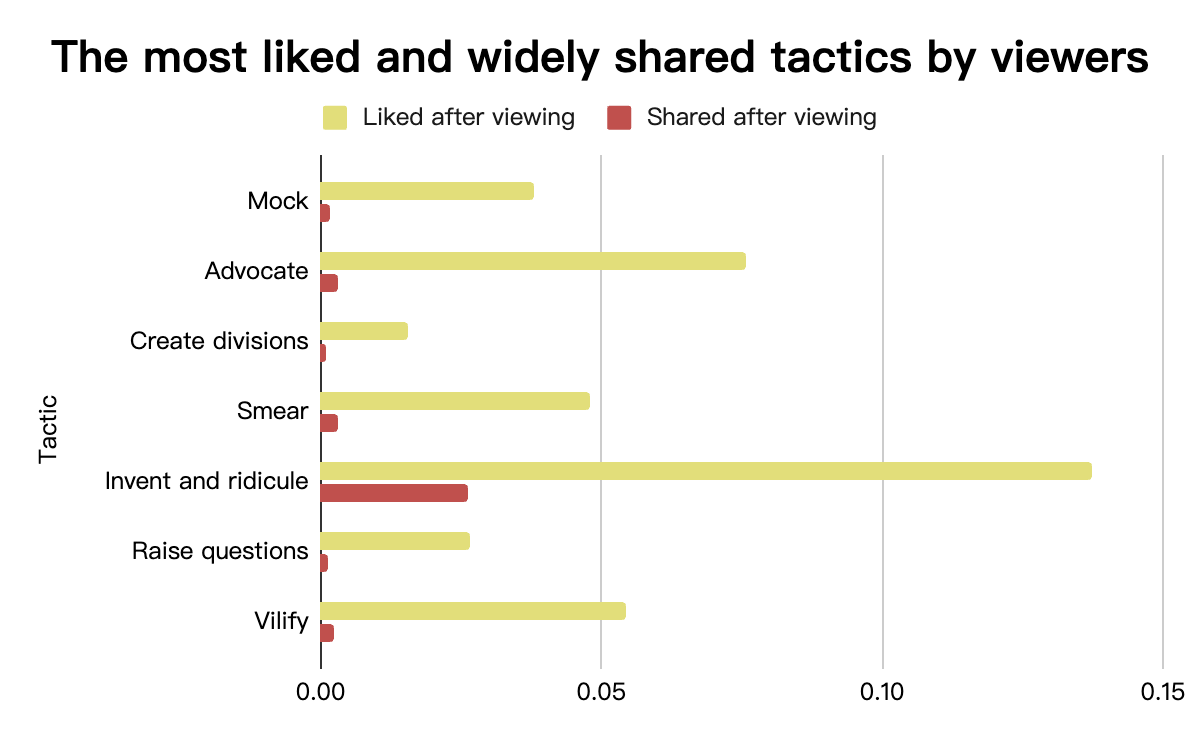

The analysis showed that the top three tactics generating the most views were "Raise questions," "Create divisions," and "Advocate." While positive, morale-boosting "Advocate" messages were attractive to audiences, the combined view rates for negative tactics like "Raise questions" and "Creating divisions" are much higher than for positive advocacy.

Although "Invent and ridicule" clips had a lower view rate, they strongly resonated with viewers. These AI mini-clips used invented events to ridicule subjects and garnered many likes, often being quickly shared widely. Their sharing rate exceeded that of other tactics.

We also observed that Reels had a higher view rate than clips from other videos, such as Facebook videos or YouTube Shorts shared on Facebook or Instagram. Data shows that the top ten viewed AI mini-clips were all Reels, with many view counts ranging from 280,000 to 680,000. The most popular clip mentioned earlier, "Old Man Climbing on a Roof," even attracted 2.43 million views, far surpassing the number of the account's followers. This suggests that the Reels algorithm could help promote viral sharing.

VII. Conclusion

This study examined AI-generated mini-clips circulating in the three months before the 2025 Taiwanese recall voting day. We uncovered a propaganda trend in Taiwan that utilized the latest AI technology: Content creators relied on affordable (mostly free) and accessible Chinese AI tools to generate many mini-clips for audiences. These clips didn't aim to tell stories or disguise their AI nature. Instead, they communicated simple messages, either to support certain viewpoints or to tarnish opponents, often using straightforward and repeated symbols to sway perceptions, bolster narratives, and provoke emotions. Sometimes, these clips presented facts with distorted interpretations that could mislead viewers.

The audience didn't appear worried about the authenticity of the messages. Many continued to watch the mini-clips, particularly those that mock politicians or arouse feelings of hatred toward political parties. Sometimes, humorous elements also increase viewership, likes, and shares.

The increasing popularity of AI-generated mini-clips, which promote narratives using simple symbols and lack detailed plots or explanations, reduces opportunities for meaningful discussions on controversial topics among social groups. This is because there is little space to present facts and reasoning. Another challenge for researchers, fact-checkers, media literacy educators, and other stakeholders in the information society is that these mini-clips are produced and circulated quickly and in greater volume.

We believe this phenomenon is not limited to Taiwan but has become a broader trend in other countries. 6We also anticipate that this phenomenon will persist in global information environments and across different events. To better prepare for this challenge, we encourage stakeholders to deepen their understanding of this trend and collaborate to develop counterstrategies.

Methodology

We conducted keyword searches using terms related to the Taiwanese 2025 recall to monitor posts and videos in Chinese-language posted on social media, especially Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube. We observed that several individual Facebook accounts and fan pages stood out for their extensive sharing of AI-generated mini-clips, particularly in terms of the sharing frequency of the clips. These mini-clips also generated a great volume of audience engagement. Considering the keywords, video content, and Facebook accounts, we collected 318 AI-generated videos and posts about the 2025 Taiwanese recall. The data covers a period from three months before the first recall voting day to one week after the vote (April 25 to July 30). We also recorded the number of views, likes, and shares for these videos. Using both qualitative and quantitative content analysis methods, we identified the themes, tactics, targets, and symbols present in these videos.

About the Authors

Summer Chen

Summer Chen is the founder of FactLink. She is an experienced journalist and fact-checker specializing in OSINT (Open Source Intelligence), fact-checking, and media literacy training. She served as the chief editor of the Taiwan FactCheck Center from 2019 to 2024, where she led the team in debunking mis- and disinformation related to regional conflicts, cross-Strait military drills, and the COVID-19 and the elections. She and her team stepped in at key moments to stop mis/disinformation and reveal how it threatened Taiwan’s democracy. She also provided fact-checking and media literacy training to journalists, teachers, and communities to help build Taiwan’s information resilience.

Wei-Ping Li

Wei-Ping Li serves as the research director at FactLink. She earned her Ph.D. from the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland and an LL.M. from the University of Pennsylvania. Her postdoctoral work at the University of Maryland examined disinformation narratives in ethnic media across the U.S. From 2023 to 2025, she collaborated with the Taiwan FactCheck Center as a research fellow. Her research interests focus on transnational disinformation and propaganda within Chinese-speaking communities. Prior to her research in disinformation and propaganda, she provided consulting on digital human rights in Asia and was also an experienced journalist working for media outlets in Taiwan.

Mary Ma

Mary Ma (Li-Hsin Ma) is the head of investigation at FactLink. She is a fact-checking specialist with five years of experience in digital investigations and OSINT. Her work focuses on election-related disinformation in Taiwan (2020, 2024), real-time fact-checking during debates, international collaboration on fact-checking projects on the Russia–Ukraine war, Chinese military propaganda, and debunking AI-driven information manipulation. She is also an experienced media literacy trainer, dedicated to advancing OSINT skills among journalists and the public in Taiwan.

About FactLink (數位素養實驗室)

FactLink is dedicated to exploring issues within the digital landscape, including social media and AI, and enhancing digital literacy, especially among Chinese-speaking communities. Besides investigating issues of the information ecosystem, it promotes digital literacy to the public and serves as a platform that connects Chinese-speaking and global communities of researchers, journalists, fact-checkers, and educators.

Brian Hioe, “In The Shadow of the Sunflowers: The Bluebird Movement and the ‘China Factor,’” Taiwan Insight, June 16, 2024, https://taiwaninsight.org/2024/06/17/in-the-shadow-of-the-sunflowers-the-bluebird-movement-and-the-china-factor/.

Austin Horng-En Wang et al., “Taiwan’s Protesters Are Against ‘Check-but-Imbalance’ and Legislative Overreach,” The Diplomat, June 1, 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/06/taiwans-protesters-are-against-check-but-imbalance-and-legislative-overreach/.

Tessa Wong, “Great Recall Taiwan: ‘Pro-China’ Politicians Survive Taiwan Vote to Kick Them Out,” BBC, July 26, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cn8185e19l4o.

Gaby Baizas, “What Can the Philippines Learn From How AI Was Used in Indonesia’s 2024 Election?,” RAPPLER, February 27, 2024, https://www.rappler.com/technology/features/lessons-philippines-how-generative-ai-was-used-indonesia-election-2024/.

Shannon Bond, “How AI-generated Memes Are Changing the 2024 Election,” NPR, August 30, 2024, https://www.npr.org/2024/08/30/nx-s1-5087913/donald-trump-artificial-intelligence-memes-deepfakes-taylor-swift.

During the 2024 U.S. presidential election, some scholars have expressed similar concerns. See Bond, “How AI Deepfakes Polluted Elections in 2024.”